This blog is part of a series celebrating Constitution Week (September 17 through 23). It's brought to you by Jon M., Career Support Librarian in the Community Engagement Office.

Let's now take a look at the other Amendments to the United States Constitution, starting with the Second. What is a well regulated militia? What is the meaning of “the people” as opposed to “persons”? How can “well regulated” and “shall not be infringed” be in the same Amendment? There are books and books and centuries of legal history that can provide clues. There are strict and loose interpretations. There are differences in opinion of what makes a militia. And those opinions are strong.

The Third Amendment is so much easier. Not having to house soldiers in a home at times of peace? Pretty easy to interpret. Then there’s the Fourth about the right to be secure in a home. That was much easier in an era without electronic surveillance capabilities, and it’s easy to find many arguments for and against expansive or limited police powers. And there’s an added element regarding the implied existence of a right to privacy, with additional overlapping questions regarding how expansive that could be.

The Fifth Amendment concerns processes related to trials, the existence of a right to trial, whether someone can be compelled to testify, and due process. And about private property becoming public property only with compensation. The Sixth is more about the rights of defendants. This provides rights to speedy trials, public defenders, and the ability to confront witnesses. The Seventh gives a right to a jury trial. And the Eighth concerns bail, fines, and outlaws cruel and unusual punishment. What is “cruel and unusual”? In the 18th Century, such things as drawing and quartering and more was a norm in some legal circles. In the 21st, there is still argument as to what is excessive regarding bail, fines, and punishment.

Then comes a curiosity of an Amendment, the Ninth.

"The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

Does this mean a right to privacy? A right to marry someone of a different race? The right to an abortion or birth control? The list of unenumerated rights is, by definition, unenumerated. But what are they? Is the Ninth Amendment a legal enigma wrapped in a camouflage paper, never to be opined about? It often seems that way. But it certainly implies a reversal of the question “Where in the Constitution does it say you have that right?” toward a different one: Where does it say the government can infringe upon it? But an implication isn’t the same as a consensus, socially or legally.

And then, to complicate that further, there’s the Tenth Amendment.

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor proscribed by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

Well, one might say that is clear as mud in regard to individual rights. Is there a coin flip to determine whether some power or right is controlled by the States or the people? A free people has often asked courts to redress grievances on such matters, and States too often ask courts to redress related grievances as well.

And from there, there are seventeen more Amendments that have become part of the US Constitution. Number Eleven concerns interstate and international trials being Federal matters. The Twelfth changed the election of the Vice President and made other changes to the Electoral Process. Then it was more than sixty years before any changes. The Thirteenth through Fifteenth Amendments followed the Civil War, and made some of the biggest changes in our history.

Ending slavery was a huge expansion of liberty. The following years weren't a time of great peace and comity for all, but a huge step was made to right a historical wrong so deep it still shames this country even as we can be proud of how far we have come since those days. And the hundred-plus years following those times, in which a right to vote and be free wasn’t so much a lived reality as a broken promise. Some insist nothing was ever wrong or that all past problems are excusable and in the past. Some love it. Some would rather not talk about it. And for some, there's bitterness. We didn’t let women vote until 1920, for instance. And even then, it was easier for some women than others. And Native Americans, the disabled, and so many others have histories of struggle to get what many consider basic rights.

There are some other portions of the Fourteenth Amendment regarding insurrection that are of current interest. And due to a blanket pardon from a post-Civil War President, there isn’t a lot of precedent from which to make any predictions. But whether the Constitution and the Amendments are to be interpreted this or that way, reading them is a great way to at least start to have an informed opinion on such matters.

Amendment Fifteen gave the right to vote to those of any color, race, or “previous condition of servitude”. Of course, as previously stated, the right wasn’t truly a right if it wasn’t enforced. And its enforcement has historically been, to put it as mildly as possible, uneven.

Over forty years later, in 1913, there came to be the Sixteenth Amendment, with which we now have income taxes. Also that year, came the Seventeenth, from which there is direct election of Senators.

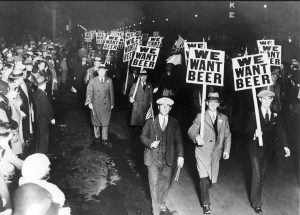

Next came the Eighteenth, which brought about Prohibition. It ended with the Twenty-First fourteen years later. A year year later came the Nineteenth, which gave women the right to vote.

The Twentieth Amendment changed the dates Congressional and Presidential terms began, when Congress had to meet, some succession issues, and additional clarifying issues. Again, this is worth a read in light of recent events.

The Twenty-Second Amendment was passed in 1951, some time after Franklin Roosevelt had broken with tradition and was elected President four times. Now the limit is two full terms, though there is some wiggle room if a Vice President (or someone else) becomes President upon the death or removal of a President who served over half a term.

The Twenty-Third gave citizens of the District of Columbia Electoral Votes. The Twenty-Fourth, in 1964, banned poll taxes, further expanding the right to vote. That was also the same year as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which furthered the reality of some of the promises of a century earlier.

The Twenty-Fifth Amendment clarified the line of succession to the Presidency. It’s why there is a “designated survivor” who doesn’t attend the State of the Union Address. The Twenty-Sixth Amendment lowered the voting age to eighteen. And the Twenty-Seventh makes it so the Congress can’t raise (or lower) its own pay, though it can modify the pay of the next Congress. That became law in 1992. And the Constitution hasn’t been changed since then.

Even with Twenty-Seven Amendments, the Constitution has had remarkably few changes over its 234 years of use. It’s a remarkably stable document, even as interpretations and arguments surround our nation. It’s endured, been tested, and been modified here and there, but its endurance has been proven. And its value has endured as well.

Additional reading: