Bless Me, Ultima smashed the rules of the white publishing world when it was published in 1972. Rudolfo Anaya, deemed the godfather of Chicano literature, picked up his pen and in seven years, after seven re-writes, he brought to life his story about the Mestizo Southwest. He embraced the historical cultural linguistic landscape of the Native American, Mexican, and Spanish New Mexico. He used Spanish and English to express the realities of religious oppression, cultural obliteration, and political genocide engaged in by the dominant Euro-American power base.

Bless Me, Ultima smashed the rules of the white publishing world when it was published in 1972. Rudolfo Anaya, deemed the godfather of Chicano literature, picked up his pen and in seven years, after seven re-writes, he brought to life his story about the Mestizo Southwest. He embraced the historical cultural linguistic landscape of the Native American, Mexican, and Spanish New Mexico. He used Spanish and English to express the realities of religious oppression, cultural obliteration, and political genocide engaged in by the dominant Euro-American power base.

He inspired people struggling through the political upheavals of the seventies to find their authentic voice as heirs to over 500 years of history. Chicanos didn’t just appear on U.S. held lands in defiance of the Caucasian usurpers. We, as Native American/Spanish “hybrids,” were here to greet the new wave of conquerors as they lay waste to traditions stretching back before the time of their diaspora. With the European continent behind them and the English language before them, new tools of appropriation were forged.

By persisting in his unique style, Rudolfo Anaya said, for all intents and purpose, İbasta!—enough! I will tell my story in my words, as seen by my eyes, as lived by my being: “We have to come out of our own experience, our own traditions, culture, roots, our own sense of language, of story and deal with that, and to hell with the white model.”

He came from a family whose Indigenous and Spanish roots predated the U.S. incursion into New Mexico in 1846. Anaya spoke Spanish—a language that had been spoken in New Mexico for nearly 340 years by the time he was born—until he started school. Once he’d mastered English, he became a voracious reader.

At his best, Anaya captured the conflicts, dreams, and belief systems of an entire region in such a way that almost 50 years later people all over the world are still reaching for copies of Bless Me Ultima. Arizona banned it in 2012 for promoting ethnic solidarity. Several other states and school systems throughout this country banned it for its use of profanity and its intrinsic criticism of Catholicism’s drive to suppress native folkways. Fortunately, no one could still the voice that spoke for the people and helped sustain the Chicano Movement of the 1970s.

In 2001, Anaya was awarded the National Endowment for the Arts National Medal of Arts Lifetime Honor by President George W. Bush. He was also awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2016 by President Obama.

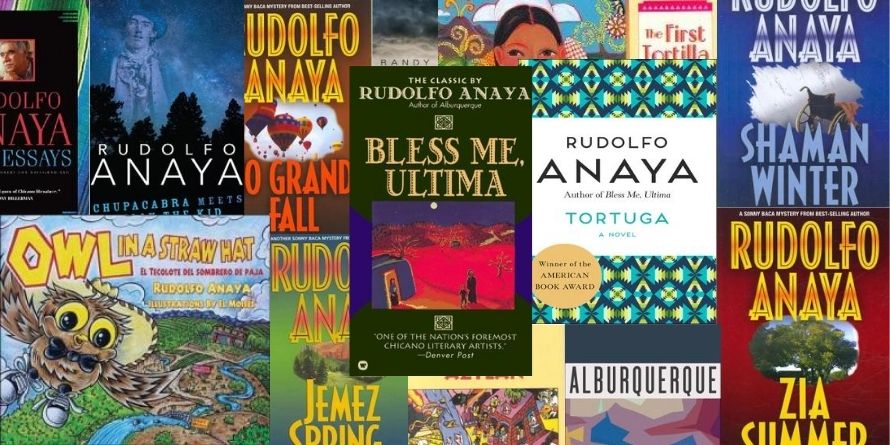

Anaya earned two Master’s degrees and was a beloved professor in the English Department of the University of New Mexico, his alma mater, in addition to publishing 16 novels, 10 children's books, 6 plays, poetry, and 12 works of non-fiction.

Aside from weaving the spiritual legacy of his forebears into everything he wrote, he was an important contributor to American literature, to the body of work defining the American Southwest, and ultimately a great American writer in his own right.

Rudolfo Anaya passed away on June 28, 2020—he will be sorely missed. Vaya con Dios…